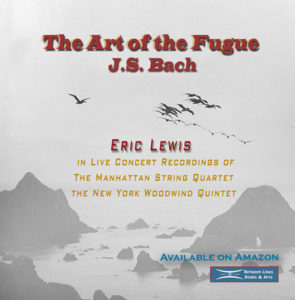

Eric Lewis—The Art of the Fugue

The Boston Globe dubbed violinist Eric Lewis “a national treasure.” Foremost American composer David Amram wrote, “I consider myself blessed to know someone as gifted as Lewis.” His praise is echoed by prominent American composer John Corigliano: “I consider Eric Lewis to be one of the most remarkable and intelligent musicians I have ever met, and I have known many, many remarkable musicians in my profession.” The New York Times described Lewis’s playing as “exquisitely phrased, heartfelt… a full rich sound made the bittersweet, almost desolate spirit of the music tangible.”

Lewis was founding member and long-time first violinist of the world-acclaimed Manhattan String Quartet. Between 1981 and 1989 MSQ served in residence and as music directors for Music Mountain in Falls Village, Connecticut. On Sunday, July 14, 1985, at 4 p.m. Lewis and MSQ joined with the New York Wind Ensemble to perform the 21 extant fugues and canons of J.S. Bach’s monumental The Art of the Fugue. This fine recording of that extraordinary evening was made by late audio engineer Howard Fawcett, who bequeathed it to Lewis; it has been recently restored in digital format by Jonathan Mullen. The recording captures the incomparable nuances and atmosphere of the live performance, and is being issued for the first time by Between Lines Books & Arts in two CDs.

This live concert recording is a tercentenary testimonial to the enduring honor and reverence heaped on the monumental series of fugues (called contrapunctus and canons), which Bach bequeathed to future musicians in his supreme effort to enliven and resurrect the ancient art of polyphonic entwining melodies in contrapuntal harmonies.

Bach’s profound and emotional approach to melody is the all-important summing up of Baroque period evolution, which began in earnest at the beginning of the 17th century with composers enamored and in ardent pursuit of drama, fantasy, and romance, leading to the invention of the genre we call opera. The Art of the Fugue (Kunst der Fuge) dates from 1749-1750, the last days of Bach’s life. He left his grand composition unfinished (16 fugues, 2 canons, 2 fugues for 2 claviers and an incomplete fugue on the name of Bach with a fantasy fugue chorale on “At his Throne”). The Art of the Fugue original score bears no indication as to the instruments to be used for its performance, so the arrangement for string quartet and woodwind quintet are an entirely proper adaptation. Its inclusion on this new Between Lines performance CD serves as a spiritual center of Eric Lewis’s over 50-year career as violin virtuoso, conductor, recording artist, teacher and chamber music leader in diverse groups like the Manhattan String Quartet, Prometheus Ensemble, Delphi, PVP, and Elysium.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s (1770 – 1827) controversial late work, always creating consternation amongst serious musicians, is called the Grosse Fugue (The Great Fugue for string quartet), and has been acknowledged as Beethoven’s testament and reverence to Johann Sebastian Bach’s final didactic work The Art of the Fugue ca. 1750. This “live” concert recording from the 1985 Music Mountain Chamber Music Series featuring the Manhattan String Quartet is a tercentenary testimonial to the enduring honor and reverence heaped on the monumental series of fugues (called contrapunctus and canons) which Bach bequeathed to future musicians in his supreme effort to enliven and resurrect the ancient art of polyphonic entwining melodies in contrapuntal harmonies.

Bach’s profound and emotional approach to melody is the all-important summing up of Baroque period evolution, which began in earnest at the beginning of the 17th century with composers enamored and in ardent pursuit of drama, fantasy, and romance, leading to the invention of the genre we call opera. These excitements are very often missed in the performance and study of Bach’s mature style, because Bach didn’t demonstrate his gifts in the form of the opera invented and framed in his time. J.S. Bach still holds title to the pre-eminent personality of the period, forming the apex and climax of the first modern romantic period we call Baroque. His rich melody-mix provided a calculus of horizontal, vertical, and deep topologies for all composers who now unquestioningly hold him in reverence like a god. He was a “musician of devotion” to the philosophies of “Christianity” and demonstrated his resolve in the 17th and 18th century churches of Germany with exquisite religious and didactic music. Secular, oratorio and operatic music would not fit into his ardent theology, but his love of the evolved 17th century forms did not diminish his infusion of its dynamism into his own chorales, passions, cantatas and instrumental works, making a sublime music filled with “song” to express his “humanist” zeal.

Bach’s extraordinary achievements to clarify the complexity of musical melody and sublimity in polyphony are expressions of his deeply felt didactic (teaching) mission and love for the next generation of children. During his time, the transition to a new style of music-making was well underway (pre-classical to classical era). Contrapuntal art and theory was quickly being moved to the outskirts of musical education in favor of the Gallant Style developed in the courts of Europe. Court purposes demanded a new emphasis on simpler musical figures consonant for an Age of the Enlightenment.

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718-1795) was among the first of Bach’s contemporary writers to expound Jean-Philippe Rameau’s theories in German, and his Abhandlung von der Fugue (1753-1754), which was inspired by his study of The Art of the Fugue. The Abhandlung was the most detailed treatise on the subject at the time (a first salvo in the resurrection of counterpoint and recognition of Bach’s very

prominent contribution). Because of Marpurg’s admiration and promotion of Bach’s work, he was the perfect choice to write the preface for the 1752 edition of The Art of the Fugue.

He importantly pointed out, “… In this work, there are contained the most hidden beauties possible to the art of music. In the minds of all those who had the good fortune to hear him (J.S. Bach), there still hovers the memory of his astonishing facility in invention and improvisation; and his performance, equally excellent in all keys, in the most difficult passages and figures, was always envied by the greatest masters of the keyboard.” He went to say: “… no one has surpassed him in thorough knowledge of the theory and practice of harmony, or, I may say, in the deep and thoughtful execution of unusual, ingenious ideas, far removed from the ordinary run, and yet spontaneous and natural.

Nothing could be more regrettable than that, through his eye disease, and his death shortly thereafter, Bach was prevented from finishing and publishing the The Art of the Fugue himself. But we are proud to think that the four-voiced chorale fantasy added here, which the blind Bach dictated ex tempore to one of his friends, will make up for this lack… A particular merit of this work is the fact that everything contained in it is set in score.”

The fact of the score form for The Art of the Fugue makes our performance transcription an authentic attempt to study the complexities of this monumental work for serious musicians and their thirsting audience to experience the holistic gesture of the work. Sharing the work with listeners felt like an act of intense telepathic longing. Bach’s music is in his intensely great musical works, like The Art of the Fugue, created to nurture a humane bond at the core of Bach’s theology of universal love. We looked to nurturing and even helping to form the “musical soul” of the audience through the performance, giving play to a constant empathetic and creative imagination taking place in a paradoxical sphere of “not knowing”.

Marpurg states in closing his preface to The Art of the Fugue, “It is to be hoped that the present work may inspire some emulation and assist the living examples of so many righteous people whom one sees now and then at the head of a musical body, or in its ranks, to restore in some measure, in the face of the hoppity melodification of so many present-day composers, the dignity of Harmony.”

Another great writer of musical matters in the 18th century, Johann Mattheson, wrote, “How would it be then if every foreigner and every compatriot risked his Louis d’or (French currency) on this rarity? Germany is and will most certainly remain the true land of the organ and the fugue.”

Carl Emmanuel Bach, the capellmeister of King Frederick’s (“Frederick the Great”) Prussia’s court and the most famous son of J.S. Bach, writes of his father in his father’s obituary, ca. 1754, “If ever a composer showed polyphony in its greatest strength, it was certainly our late lamented Bach. If ever a musician employed the most hidden secrets of harmony with the most skilled artistry, it was certainly our Bach. No one ever showed so many ingenious and unusual ideas as he. He always wove strange melodies, but were varied, rich in invention, and resembling those of no other composer, with his preference to music that was seriously elaborate, and profound; … he could take in all the simultaneously sounding parts [of the score] at a glance. … Bach was the greatest organist and clavier player that we have ever had. The Art of the Fugue is a fitting end to a very great composer’s life.”

The Art of the Fugue (Kunst der Fuge) dates from 1749 – 1750, the last days of Bach’s life. He did not finish this monumental composition (16 fugues, 2 canons, 2 fugues for 2 claviers and an incomplete fugue on the name of Bach with a fantasy fugue chorale on “At his Throne”). The Art of the Fugue bears no indication as to the instruments to be used for its performance; so our arrangement for string quartet and woodwind quintet are an entirely proper adaptation. Its inclusion on this new Between Lines performance CD serves as a spiritual center of Eric Lewis’ over 50-year career as violin virtuoso, conductor, recording artist, teacher and chamber music leader (in diverse groups like the Manhattan String Quartet; Prometheus Ensemble; Delphi; PVP; and Elysium).

I must mention the deep gratitude I and the members of the MSQ feel for Samuel Baron, iconic American flutist, Bach scholar par excellent, and caring teacher for his lifelong researches he shared with us, illuminating the works of Bach which culminated in this transcription of The Art of the Fugue , an expanded chamber music version. You are listening to a “live” concert tape that was the culmination of rehearsal and intense study for all the performers on stage: Manhattan String Quartet (Eric Lewis, 1st violin; Roy Lewis, 2nd violin; John Dexter, viola; Judith Glyde, cello), New York Woodwind Quintet (Samuel Baron, flute; David Glazer, clarinet; Donald MacCourt, bassoon, William Purvis, horn; Ronald Roseman, oboe) and a full house of ardent J.S. Bach lovers at the Music Mountain Radio Broadcast, Sunday, July 14, 1985, 4 p.m. from Gordon Hall at the Music Mountain chamber music estate in Falls Village, Connecticut.

The MSQ served as Music Mountain’s quartet-in-residence and music directors for those golden years of chamber music immersion from 1981 to 1989.

Eric Lewis

Oct. 30. 2015