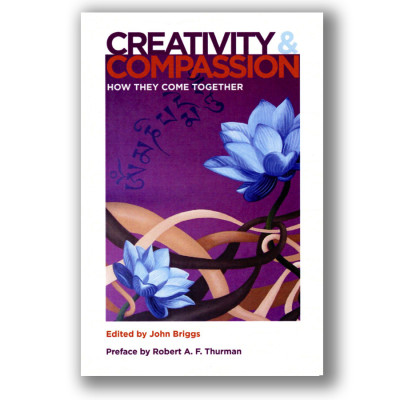

Creativity & Compassion

How They Fit Together

Edited by J. Briggs

A collection of original essays by Buddhist scholars, educators and creative artists exploring the intersection of compassion and creativity, with an introduction by Tibetan Buddhist Scholar Robert Thurman. Topics include: What do the words compassion and creativity mean? How are creativity and compassion interrelated? Is compassion a creative process? How is compassion present in both the experience of art and the creative process of making art? Are creativity and compassion both present in the highest achievements of diverse fields—from medicine to poetry? are there ways in which creativity and compassion may be applied in daily life, professional fields, and collective action?

From the General Introduction to Creativity & Compassion.

In the West creativity has long been a vital concept, with largely positive overtones. At the same time, the concept engenders considerable popular ambivalence and confusion. On the one hand, creativity is considered frivolous so that arts programs are the first to be cut in a budget crisis. On the other hand, creativity and innovation are considered essential economic assets. Creativity is considered a healthy means of “self expression.” But creativity is also associated with being willfully nonconformist and with the narcissistic aspect of personality, as in the popular expression disparaging someone for “just being creative.” We depend on creativity to solve problems and yet creativity is often thought of as a little “crazy,” and people involved in sustained creative activities are regularly assumed to be psychologically unbalanced. Though this stereotype is demonstrably untrue, it is persistent and no doubt derives from the fact that creative activity breaks molds and allows people to “think outside the box.” That, of course, is just what people are also urged to do—think outside the box and outside the routines of thought, the clichés of opinion and solution. We feel ambivalent, though. We’re afraid because such thinking seems uncomfortably abnormal.

What is creativity? Here’s a composite definition:

Creativity brings something new or re-newed to the world. It connects the previously unconnected or rejuvenates previous connections injecting them with new vitality as if they are being freshly discovered. Creativity is an immensely powerful human capability. It is the source of change in the world that is made and understood by human consciousness. It’s generally recognized that insight is a form of creativity, as in “The Buddha had the insight about the nature of reality.” Examples of creativity include invention of new technology, discovery of new scientific truths, making works of art that express the renewed spirit, creativity in nature as the evolution of new forms and behaviors, insights in human thought that dispel ignorance or illusion. Humans are creative animals. We invented clothing, fire, religion, mathematics, language, culture itself.

The sustained creativity that has produced the great music, visual art and literature of the world shows the connection between creativity and compassion. These great creative works elicit our recognition of the human condition. Without saying so directly, they evoke our compassion for human suffering and for our sense of identity with every thing and everyone.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has said: “Compassion compels us to reach out to all living beings, including our so-called enemies, those people who upset or hurt us. Irrespective of what they do to you, if you remember that all beings like you are only trying to be happy, you will find it much easier to develop compassion towards them. Usually your sense of compassion is limited and biased. We extend such feelings only towards our family and friends or those who are helpful to us. People we perceive as enemies and others to whom we are indifferent are excluded from our concern. That is not genuine compassion. True compassion is universal in scope.”

In another context, the Dalai Lama said: “Usually when we are concerned about a close friend, we call this compassion. This is not compassion; it is attachment. Even in marriage, those marriages that last a long time, do so not because of attachment—although it is generally present—but because there is also compassion. Marriages that last only a short time do so because of a lack of compassion; there is only emotional attachment based on projection and expectation. When the only bond between close friends is attachment, then even a minor issue may cause one´s projections to change. As soon as our projections change, the attachment disappears, because that attachment was based solely on projection and expectation.”

Novelist William Faulkner said in his Nobel Prize speech in 1949, during the rise of the cold war and the atomic age:

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

“He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed—love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.”

The kind of creativity expressed in the arts puts us in touch with this sense of universal connection that is impersonal and yet passionate; art shows that our deepest connection to the world is not based on attachment.

Zen Buddhists argue that the creative state of mind is “the beginner’s mind.” Zen master Shunryu Suzuki writes that “the beginner’s mind is the mind of compassion. When our mind is compassionate, it is boundless.” The Dalai Lama sees compassion as synonymous with genuine “happiness”…